REMEMBERING THE TWO JACKS: CS LEWIS AND JOHN F KENNEDY

My diary is usually a blank since Covid and becoming a Carer, apart from the inspiring reminders to ‘Put bins out’ or ‘Do food order’. But that wasn’t the case on 22 November 2013.

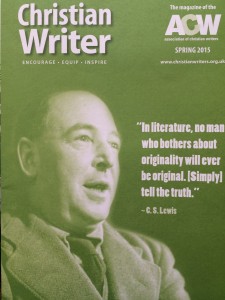

It was the fiftieth anniversary of the deaths of author and Professor C S Lewis and author and President John F Kennedy. All Lewis fans know that he died on the same day as the terrible assassination of Kennedy, and so the fact didn’t get much publicity at the time as a result.

That any of these events should have had an effect on my diary entries for 2013 seems increasingly strange as the years go by. But it caused an unlikely clash: I was supposed to be in two places at once.

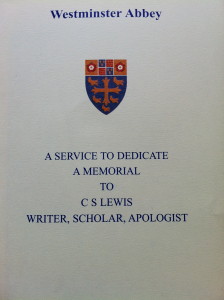

Firstly, I was invited to be part of the celebration of C S Lewis’ life at the inclusion of a memorial to him in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey in London. This was later to be published as:

Secondly, I was invited to the celebration of the life of President Kennedy being held on the same day at the memorial to Kennedy at Runnymede in Surrey.

The Kennedy Memorial Trust

Back in 1984 I had been awarded a scholarship to Harvard by the Kennedy Memorial Trust, and it was this Trust that had been set up in 1965 to acknowledge the British people’s huge outpouring of grief at the President’s death. The two parts were to be a “memorial in landscape and stone” at Runnymede and a ”living memorial” in the form of the Scholarship programme for around ten postgraduates a year to go from the UK to Harvard or MIT. There are now over five hundred of us. [1]

Runnymede near Windsor was the scene of the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215, the ‘Great Charter of Liberty’ extracted by the barons from King John, which meant even the king was to be subject to the law. In a sense it was the beginning of parliamentary government and the inspiration for ideas of political liberty around the world, and it was here the official memorial stone to the President was unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II in 1965. The ceremony was attended by members of the Kennedy family, and the land that holds the memorial was granted to the American people in perpetuity. The event was largely organised in 1965 by David Ormsby-Gore, Lord Harlech. He had been one of Kennedy’s best friends and British Ambassador to America (and who, strangely enough, was to interview and then award me the Kennedy Scholarship in 1985 on the very day he too was to die tragically, in a car crash on the way home).

There is a video of the moving ceremony at Runnymede and the surrounding countryside: the walk through a wicket gate and then a wood and then the path to the seven ton block of Portland stone, which were all part of the memorial and designed to be like ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ for the visitor.

It reminded me of Addison’s Walk at Magdalen College Oxford where Lewis had his spiritual breakthrough in his talk with Tolkien and Dyson.

The two memorial stones are similar in some ways, including quotes from the men themselves, though on a different scale:

Lewis at Westminster Abbey

Of course I wanted to be at both events in 2013. But since I’d been asked to be part of a panel discussing Lewis’s influence today, but would only have been a spectator at the Kennedy event, then it certainly made sense to be at Westminster Abbey.

Plus the fact that Lewis had influenced my spiritual and academic life to a far greater extent than Kennedy, although the scholarship to Harvard was fantastic and led me to spend four years in America as a result.

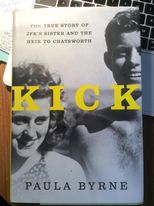

I tend to be reading books by or about CS Lewis most of the time, but by sheer coincidence I’ve just finished a different book that instead involved Kennedy, as it was the biography of his ‘forgotten’ sister Kathleen, known as ‘Kick’ [1]

Kick and Jack

When Kick was born in 1920, Jack was already two and a half. They were to become best friends in a family of nine children and remained so throughout life, although Kick’s was to be cut short by tragedy even before her brother. At her untimely death in a plane crash in 1948 she was already a widow. She had married William ‘Billie’ Cavendish, the Marquess of Hartington, the son of the Duke of Devonshire, but Billie had been killed in heroic circumstances in the Second World War. She really could have wandered around the magnificent Chatsworth House in Derbyshire and whispered ‘Of all this I might have been mistress’, like Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice.

It was partly through her social success with the English upper classes, backed up by their father being the American ambassador to Britain, that mean Jack Kennedy had access to the rich and powerful in the UK. I was interested to read how pro-British he was, especially in his admiration of Churchill, for example, studying his speeches.

Irish Roots

Of course Kennedy was also keen to explore his Irish roots in several Irish counties. The fact that his sister had married into the Devonshires also meant that they had invitations to their Irish property, Lismore Castle in County Waterford, which also would have belonged to Kick’s husband, had not tragedy intervened. The extent to which the Kennedys had woven themselves into British life before the War really surprised me. It also made me think more about CS Lewis’ Irish roots in Belfast and the ‘pull’ that Ireland has for the many millions who have ancestry there, including my own via a grandmother and her family, the MacNabs. For both CSL and JFK, Ireland was ‘home’.

The Devonshires and Chatsworth

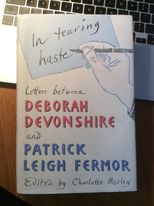

I now realise that this makes sense of a photo I once saw. It was of President Kennedy’s Inaugural parade in January 1961, and there right on the front row was Deborah, the Duchess of Devonshire, right next to the President. The photo is in a book of Debo’s letters [2].

At the time everyone wondered who on earth this woman was. But she, as Debo Mitford, had been great friends with Kick Kennedy when Kick had dated Billie, the Marquess of Hartington, and Debo had dated his younger brother Andrew, so they hung out as a foursome before the War. When Billie was killed in 1944, Andrew inherited the title and therefore became the next Duke, and owner of Chatsworth and numerous other stunning properties. If death hadn’t intervened for Kick in 1948, aged only 28, she would have been the ‘new’ Duchess, so in a sense Debo was a substitute for Kick at the Inauguration.

JFK had been so upset at the death of his sister that he only visited her grave at Edensor near Chatsworth years later, just months before his own death.

The Two Jacks as Young Readers

But one of the things that surprised me the most was how similar the two Jacks had been in childhood and early youth, in the sense that both had been loners much of the time and voracious readers, and of course it was this that was to give them the edge in their subsequent careers, forming their main interests and pursuits. I already knew about CSL’s reading habits, but was amazed at how frequently JFK had been ill and in hospital or bed bound whilst growing up and had therefore read so deeply. Both had been deeply influenced by their boyhood reading on the history of Chivalry, for example. And later on JFK’s father’s appointment as Ambassador to the Court of St James, and the political and aristocratic contacts that this provided in the UK, meant that Kennedy could as a young man meet the political and cultural heroes he had only encountered in his reading.

Christmas at Chatsworth

At Christmas I usually re-post my blogs about the wonderful Narnian ‘Christmas at Chatsworth’ event I also attended in 2013. Of course the main focus of this is from the creative imagination of Jack Lewis, as each room at the stately home was magnificently decorated with characters and themes from the ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’.

But this year, as I look again at these Christmas photos, I will definitely be thinking of the Kennedy connection as well, of Kathleen and her younger brother Jack, who also wandered around Chatsworth in awe. I will remember the future President, and Kick his sister who should have been a Duchess, and the events that forever link the two globally famous Irish Jacks, the Professor and the President.

NOTES

[1] For Kennedy Memorial Trust, see https://www.kennedytrust.org.uk/

[2] Paula Byrne, Kick: The True Story of JFK’s Sister and the Heir to Chatsworth (HarperCollins, 2016)

[3] For Debo & JFK, see https://themitfordsociety.wordpress.com/2013/11/21/debo-jfk/

and (ed.) Charlotte Mosley, In Tearing Haste: Letters between Deborah Devonshire and Patrick Leigh Fermor (John Murray, 2008) re Inauguration.

For the short film about the Kennedy Memorial, see

https://www.kennedytrust.org.uk/display.aspx?id=1870&pid=0&tabId=230

For the Westminster Abbey Institute Symposium from 21 November 2013, see